“Wardy Surfboards,” Part 1

Introduction

Frederick Julian Wardy, born on November 18, 1934, in Los Angeles, spent the late 1950s through the mid-1960s making balsa and foam surfboards that became part of the lore of the California surfing world. Many are now in private collections. In 1959, he opened Wardy Surfboards in Laguna Beach, where production and sales occurred, and additional outlet shops followed, including one in Pasadena the same year. Wardy’s advertising writings and imagery form part of his creative achievement. In 1967, he went on to pursue a career as an artist.

“Uncommon Skill & Meticulous Attention,” an article by Lance Conragan, appeared in the June/July 2023 issue of The Surfer’s Journal. https://www.surfersjournal.com/editorial/frederick-wardy-uncommon-skill-meticulous-attention/

Conragan, a longtime surfer, the owner of many boards, and a writer about surfing, takes an overview of Wardy’s surfboard making years and those as a painter and sculptor. He has been interested in Wardy boards since his teenage years in the 1960s.

Origins of Wardy Surfboards

Part of a large, warmhearted, three-generational household, Wardy charted his own path, even as a child growing up in Highland Park, a multi-ethic neighborhood of Los Angeles. Independent, tenacious, and work-oriented, he defined and pursued his own interests. “No one ever asked me where I was going or what I was doing,” he has said.1 He became a strong and confident swimmer by frequenting pools in Los Angeles, which required taking two or three buses but where lifeguards often recognized his athletic abilities and guided him in strengthening exercises. He also swam and body surfed at beaches in the Los Angeles area and down in Long Beach where he used to swim out to the breakwater and along its rocky formations.

Wardy developed an enthusiasm for surfing while he was in high school after watching surfers in action at Malibu. He acquired his first board second-hand, perhaps one by Dale Vezly, a California surfboard maker who had opened a shop in Manhattan Beach in southwest Los Angeles County in 1950. Trying the board out at Malibu, and being thrown hard by a wave, he sought out beaches with smaller waves “to get the hang of it” and practiced whenever he could, sometimes working with his board in a neighbor’s swimming pool.

These early swimming and surfing experiences stimulated Wardy’s interest in designing and making surfboards. After graduating from Cathedral High School in Los Angeles and while at the University of California (UCLA) in 1953 and 1954, he began teaching himself the steps involved as he worked in his grandparents’ basement and backyard in Highland Park. He remembers the time well:

I knew what I wanted to make but didn’t know anything about the construction. I had to find supply sources and, without equipment, resorted to taking inner tubes and cutting them into big bands to use during the process of gluing the balsa strips together. Once I saw that I could make the boards, I started to sell them, for about $100 each. Neighbors and others who walked by the backyard fence began to buy them. The business came about because I could see that I had a knack for it.

In 1955, Wardy enlisted in the Army, spurred by the opportunity to receive financial aid for higher education, and did some competitive swimming, preceded by rigorous training. When his military duty was completed in 1957, he returned to UCLA and continued to make surfboards in Highland Park. In 1957, he went to Hawaii to learn more about surfing the big waves there and to enroll in philosophy courses at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. He found a job selecting balsa wood for a board maker whose shop was near the beach at Waikiki. Wardy surfed there regularly.

Once back to building his own boards, Wardy’s sales increased, and he soon formally established his business:

I got the idea of having a place of my own to make surfboards, to have a real business. I didn’t know Laguna Beach; I don’t think I’d ever been there. I had been going north of Los Angeles, mainly to the Malibu area for surfing. There was spot, though, called Wind and Sea [a.k.a., Windansea]—it sounded pretty romantic to me—north of San Diego, so I decided to go there first, down to the coast north of San Diego. I didn’t like it, however, so I continued up the coast, got to Laguna Beach, and spotted this barn-like building. I walked in and found out that it belonged to a nearby lumberyard owner. I rented the place, inexpensively. After I did that, I was fully committed.

There was no other surfboard shop in Laguna Beach.

Wardy opened the shop (Fig. 1) in early 1959 at 525 Forest Avenue, not far from Main Beach.2 At first, he worked twelve-hour days, seven days a week, taking breaks only to surf or play volleyball with a friend at the local high school. He remembers:

In the beginning, I did everything myself, kept a ledger on the counter, and buyers would just write in their names and the size of the boards they wanted. For a little while, I lived and worked in the back of the shop. It was very exciting getting a business started, such a learning process. I was near the ocean, people were friendly—surfers coming in to exchange ideas. Everything fell into place. I built two surfboards and sold them almost immediately. In time, I had a whole crew working with me

Fig. 1. Wardy Surfboards shop, Laguna Beach.

A Crew of Craftsmen

Wardy gradually hired a group of young men who were or became shapers, glassers, sanders, and fin makers based on their interests and talents. By 1961 or early 1962, they numbered six. In April 1962, he posed with them for a series of photographs taken at Irvine Cove, about one-quarter of a mile north of Main Beach and within the town of Laguna Beach. The photographer was Ron Stoner, a young professional who worked independently and for Surfer magazine.

Fig. 2 and its closeups, Figs. 3 and 4, show the group, with left to right: Wardy, Bob Machado, Larry Bailey, Stuart Burgess, Ron Sizemore, John Thurston, and Bob Spencer (a.k.a. The Fly and later Jean-Pierre van Swae). Sizemore’s eye patch due to a surfing injury has Wardy ’s name on it. In another photograph from the series (Fig. 5), the men appear relaxed and having fun.3

Fig. 2. Wardy and crew, at Irvine Cove, Laguna Beach, in 1962, photograph by Ron Stoner.

Fig. 3, Detail of Fig. 2.

Fig. 4, Detail of Fig. 2.

Fig. 5. The same day and location as Figs. 2 to 4.

Fig. 6 was used for an advertisement in Surfer (May/June 1962) entitled “The Emblem and the Craftsmen,” referencing Wardy’s logo, which is visible at the end of the board in the foreground.4 In Fig. 7, an enlarged board with the design elements of the logo, colored green and yellow, towers over the group in a full-page ad on the inside back cover of SI Surfer Illustrated (winter 1963).5 Forty years later, the photograph, minus the board but including the names of those pictured, was reprinted on a full page in Surf Culture: The Art History of Surfing (2003) by Bolton T. Colburn, published in conjunction with an exhibition at the Laguna Art Museum.6

Fig. 6. “The Emblem and the Craftsmen,” Surfer (May–June 1962).

Fig. 7. SI Surfing Illustrated (winter 1963).

Wardy had his crew members wear black pants with white shirts, black ties, and black shoes for the photographic series because, he says:

Surfers were sometimes considered louts, so I had everyone dress up for that photo. These were young guys who worked mainly part time. They were all surfers, and some were surfboard shapers who had previously worked for others.

Sizemore and Spencer were both in high school at the time.

When Spencer first walked into Wardy Surfboards, Wardy handed him a piece of sandpaper to do some light sanding. He sanded right through the resin down to the foam surface beneath it. “People have to learn,” Wardy remarked when he and Spencer, who became a specialist at making fins, recently recalled the incident. When Sizemore walked in, Wardy handed him a broom. He started as a floor sweeper and became a sander. Sizemore remembers what it was like at Wardy Surfboards:

Wardy surrounded himself with people who were genuine craftsmen and who took an extreme amount of pride in what they were producing under his employment. Everyone took a lot of time and effort with what they were doing for him. It was a genuine pleasure to work for Wardy.

Sizemore has also emphasized that the crew members worked together easily, ascribing that to the fact that “They were nice people.”7

Wardy made a point of the expertise of his crew and their pride in their work in the text of “The Emblem and the Craftsmen” (Surfer, May/June 1962):

The men who build these boards are professionals who are proud of the product they stand behind. In the Laguna Beach shop where these boards are built, each man performs his duties with patience, pride, and meticulous attention to detail thus insuring controlled quality throughout the entire process. These men endorse the fact that there are no finer surfboards than those that bear the Wardy emblem.8

Wardy would be widely recognized as having some of the best specialists in the surfboard making business, who either came to him with some experience or were trained by him. Bailey gained a reputation for his skill as a shaper and glasser; Burgess as an expert at shaping and sanding; and Spencer as a fin specialist. Crew members hired later included Don Donfrey, known for his methodical shaping. Several members of Wardy’s crew, including Machado, Spencer, Del Cannon (shaper), and Pat Curren eventually went on to work for others or opened their own shops.

Types and Production of Wardy Boards

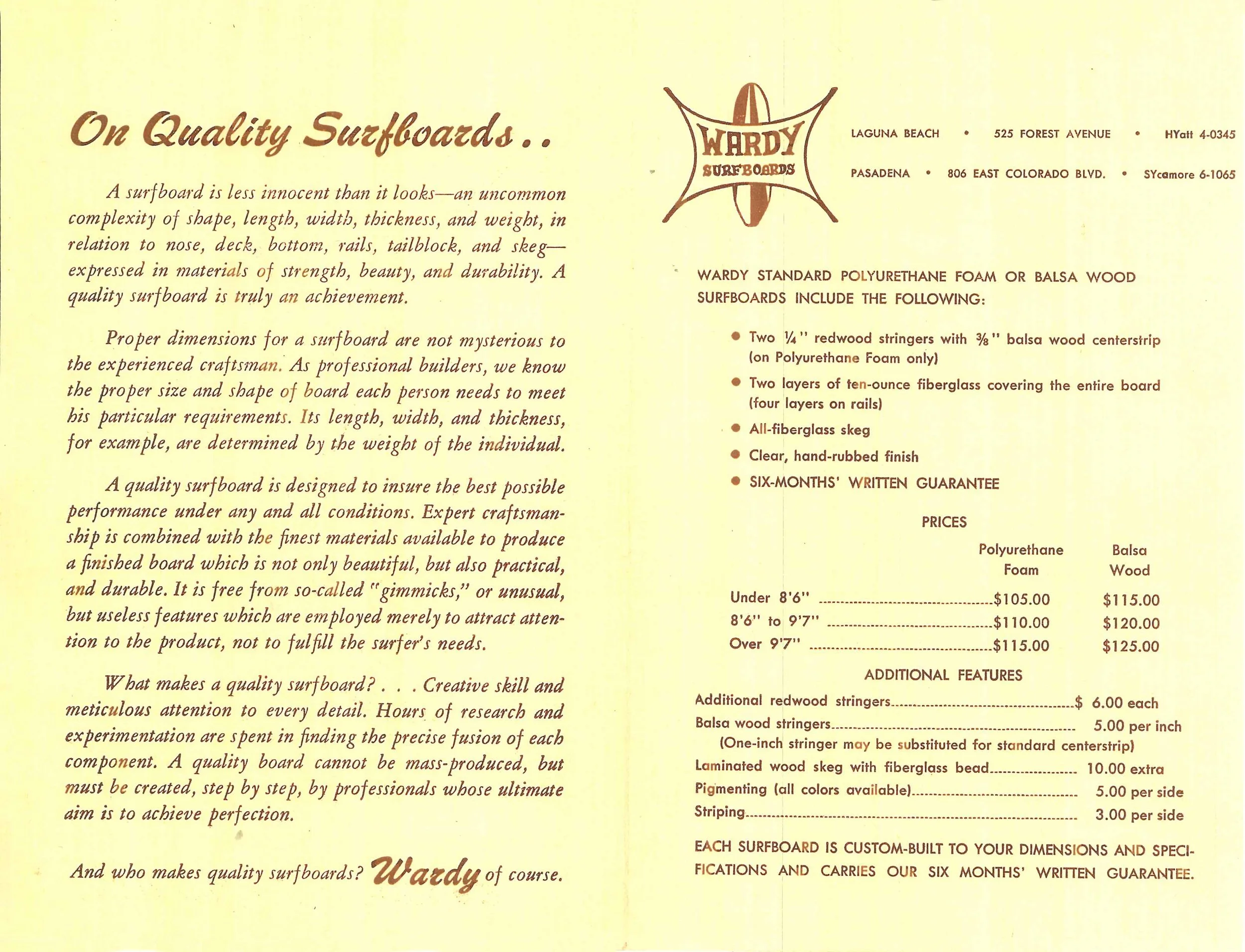

The process of making surfboards in the 1960s, before the advent of machines for shaping them, was a complex one. In “On Quality Boards. . . . (Surfer, spring 1962),” Wardy explained this:

A surfboard is less innocent than it looks—an uncommon complexity of shape, length, width, thickness, and weight, in relation to nose, deck, bottom, rails, tailback, and skeg—expressed in materials of strength, beauty, and durability. A quality surfboard is not easily attained.9

Balsa Boards:

How surfboards are constructed, including details of each step, helps one to appreciate the skilled craftsmanship required and the aesthetic judgments involved. Wardy’s first boards were made of balsa, which is lightweight and buoyant, weighing from eight to fourteen pounds per cubic foot, depending on its density. Balsa longboards produced at Wardy’s shop usually measured between nine and ten feet. He advertised custom-made balsa boards until at least September 1963. Those boards are difficult to locate today in part because no Wardy board had a tether, a rope coming from a hole in the fin to connect to the ankle of the surfer to prevent loss when the surfer dove into a wave.

Examples of Wardy’s balsa boards include Figs. 8 to 10 from the collection of the Surfing Heritage and Culture Center in San Clemente, California, and Figs. 11 to 15 from two Southern California private collections. See Appendix B for other views of these boards.

Fig. 8. Balsa. Collection of Surfing Heritage and Culture Center, San Clemente, CA.

Fig. 9. Back of 8.

Fig. 10. At the Huntington International Surfing Museum, “Surf2Skate” exhibition, 2018.

Fig. 11. Balsa, priv. coll.

Fig. 12. Close view of 11.

Fig. 13. Balsa, 10', priv. coll.

Fig. 14. Back of 13.

Fig. 15. Balsa, 7'7″, Collection of Jim Cocores.

Working with balsa was time consuming. Bundles of it, four to five feet in diameter, were ordered from General Veneer, a Los Angeles company that received its supply from South America. The metal strapping holding the wood together—pieces more than nine feet long—first had to be cut, and then “the fun began,” says Wardy. Pieces were matched with as little waste as possible and with consideration given to length, the measurements of the sides of each piece (often four by four inches or so), and the weight (which depended on density of the balsa and which affected balance, a critical factor). The varying shades of the wood, which could run from oatmeal to tan, sometimes with a pink or yellow hue, were an aesthetic concern.

On the specific care involved in putting the pieces together, Wardy has said: “We had to balance the wood so that it made sense weight-wise; a two by four could be four, five, or six feet long and could weigh five or ten pounds. We were constantly taking balance into consideration, both with regard to length and to width.

After gluing, a “drawing knife” was used to whittle down the surface. Wardy preferred a forge-shaped blade, which he had asked a local blacksmith to create from a machete that he gave him. The more subtle shaping followed, with a hand plane or with an electric plane. Wardy worked with a hand plane from Japan that he considered special. Gluing of the balsa could take about four hours, and all the stages of shaping, which included sanding, required an additional six to eight hours.

Next was glassing, which was also done with Wardy’s foam boards. It involved the precise application of two layers of flexible fiberglass of slightly different lengths to a board’s surface. This came to be known as the “double glassing technique” and was later taken up by other surfboard makers. In Petersen’s Yearbook (1963), a major surfing publication of its time, Richard W. Graham writes in the “WARDY” section of his article “A Look at the Boards”: “All Wardy boards are hand sanded where the two layers of glass overlap, according to Bob Machado, one of the industry’s top glassers. This hand sanding of the overlap causes the glass sheets to blend more than if it were merely cut with a blade.”10

As a final step, liquid resin, stored in 55-gallon drums, was mixed with a catalyst to make it harden when applied to the fiberglass. This was the final protective surface. Wardy explained the details of the use of resin in “A Few Words on Surfboards” (Surfer, Dec. 1963/Jan. [1964]): . . . we use an isopthalic [sic, isophthalic] resin which is 25% stronger than most resins; double layers of tightly woven ten-ounce fiberglass.11

Some of the glassing was done at an auxiliary workshop along the nearby Laguna Canyon Road going inland.

Foam boards:

In the early 1960s, polyurethane foam was replacing balsa in board making. Wardy’s foam boards were lighter than the balsa ones, had more volume, were not as long (generally measuring eight to nine feet in length), and had wider, rounder noses. As with the balsa boards, the larger the board, the greater the flotation. Wardy added beach break [beachbreak] boards to his shop’s production in 1965 as indicated in Figs. 122 and 123 (Surfer, July 1966; Sept. 1966) showing Del Cannon riding them with flare.12 Although still considered longboards, such boards were shorter than other longboards and were used on waves breaking onto shallow sandy bottoms or sand bars.

On making the foam boards, Wardy has explained:

You would buy a piece of foam of about nine and a half feet and then cut it down to varying lengths as far as to nine feet to shape it. It presented a whole other process, faster than doing the fusing of pieces of balsa. It was a completely different surface to lay the fiberglass on and was much lighter. You did not have to be concerned with balance, as with wood. You could see immediately it was the way to go—pretty, light surfboards and cheaper than the wood. I still made wood boards but charged a little more.

The construction process began when long, rectangular pieces of polyurethane foam called blanks were ordered from two major producers in Southern California: H. Walker Co., owned by Harold Walker, who was one of the first dealers in foam blanks for surfboards, and Clark Foam, established in 1961, and owned by Gordon Clark. Clark Foam was originally located in Laguna Canyon, not far from Wardy Surfboards.

At the time of ordering, the supplier was given specifications for the overall placement of and widths, lengths, and mediums of any stringers requested. Wardy’s basic foam boards, whether for stock or by request, were plain without any stringer or with only one, as in Figs. 16 and 17. Occasionally, a balsa board would have a stringer of, say, redwood. The arrangement of the stringers was either predetermined by a list of specifics from the supplier or was the result of special orders from Wardy surfboards. Through the latter, considerable originality was possible and has subsequently pleased many collectors. Whether predetermined or special ordered, the blanks would arrive with the stringers set in but not flush with the foam. An initial sanding was required and then the glassing, and resin, including coloration when desired, followed. With some boards, lines were added with a Radiograph pen.

Fig. 16. 9'4″, priv. coll. Fig. 17. 9'6″, priv. coll.

Among foam boards with multiple stringers are Figs. 18 to 21 and Figs. 22 and 23 (details).

Fig. 18. 9'6″, priv. coll.

Fig. 19. 10'4″, priv. coll.

Fig. 20. 9'6″, priv. coll.

Fig. 21. 10'8″, priv. coll.

Fig. 22. Detail of 18.

Fig. 23. Detail of 21.

The boards in Figs. 24 to 26 are currently or were in a major collection of Wardy boards. Its owner has said that he likes the “simple, clean, and functional design” of Wardy boards and the “unique qualities of their stringer configurations.”13

Fig. 24. Wardy boards on a rack, priv. coll.

Fig. 25. Wardy boards on a rack, priv. coll.

Fig. 26. Wardy boards on a rack, priv. coll.

Besides stringers, foam boards were sometimes given tail blocks. These are small horizontal bands of wood or fiberglass, the latter often the color of the fin. A tail block protected the tail to a degree but mainly added originality to the board, as in Figs. 27 to 29.

Fig. 27. Tail block of Fig. 21.

Fig. 28. Tail block of Fig. 20.

Fig. 29. Tail block of Fig. 45.

By contrast, a fin (a.k.a. skeg), whether for a balsa or foam board, is critical to the functioning of a surfboard in that it holds the surfer into the wave. Wardy recalls being “particularly curious” about fins and fascinated by “their variety in shape, placement, and beauty.” When he and his crew experimented with and then made wood fins, mainly for balsa boards, a single unit or several fused units (usually varying in shades of brown) would be covered with fiberglass and resin. Fig. 30 shows the extension of the fiberglass to protect the fin from damage, including from water.

Fig. 30. Fin of Fig. 10.

Figs. 31 to 42 represent various fin types on foam boards, which sometimes were given wood fins but mainly had fiberglass ones. They vary in shape, however subtly, in the degree of a curve into the board, distance from the tail, and color. [According to Wardy and others, the expressions “D” fin and “reverse D fin” in describing some of the shapes were not used when these were made.] If too long, a fin might scrap on the sand or rocks as the surfer entered the water; too short a fin might cause the surfer, whether a beginner or an experienced rider, to fall out of the wave. In Appendix B, full views of boards are shown, along with their fins pictured here.

Fig. 31. Fin.

Fig. 32. Fin.

Fig. 33. Fin.

Fig. 34. Fin.

Fig. 35. Fin.

Fig. 36. Fin.

Fig. 37. Fin.

Fig. 38. Fin.

Fig. 39. Fin.

Fig. 40. Fin.

Fig. 41. View of fins on a rack, priv. coll.

Fig. 42. View of fins on a rack, priv. coll.

In making fiberglass fins at Wardy Surfboards, the technique involved using sheets of fiberglass measuring four by four feet, which would be pressed together to squeeze out bubbles. Bob Spencer (The Fly) rigged up a light table that enabled him to see every bubble in the fiberglass layers of the bonded sheets. Sometimes, he went into the shop at night and turned on only the light beneath the table in order to clearly see and remove every bubble, no matter how small. “I was obsessed with making the perfect fin,” he told Wardy and others in 2023.14 Resin, plain or colored, and with a catalyst to harden it, would then be applied to the sheets. Six to eight fins would be cut from each unit.

Wardy personally rode many boards to test the fins and enlisted both Bob Sizemore, who participated in surfing competitions, and Dave Martin, who “was a good rider and felt things well,” according to Wardy. He even experimented with a narrow rectangular fin and discovered that it worked fine. There was also experimentation with removable fins, which involved putting a fin supported by dowels into a groove that would allow it to be moved several inches up and down the board.

Foam boards with color:

Although Wardy personally preferred plain boards, being primarily interested in functionality and form, he did become “curious” about how his boards would look with color, and early in his production years also made colored boards, not only for customers but also for stock. At first, he tried out what he has referred to as “splash jobs.” He would pour on three or four different colored resins, blend them, and spread them to get a “dramatic effect.” Wardy remembers the results as being “abstract, beautiful, and peculiar.” Not many such boards were made, however, in part because “they were a lot of trouble and too time-consuming.” Some of these boards comprised an exhibition at a department store in Pasadena in the early 1960s, Wardy, Sizemore, and others recall. Wardy maintains that the painterly qualities of boards reputedly by him that he has seen in photographs bear no resemblance to the painterliness of his “splash jobs.”

The surfboard blank maker Walker developed a method to infuse color into a foam blank, which resulted in certain colors—yellow, green, and light blue—taking fairly well to the process, according to Wardy. He experimented with this type of Walker blank on only one or two occasions but did not continue to use it because he thought that the color weakened the foam.

The application of color to plain foam blanks required careful attention in the mixing of colored resins and to the occasional addition of a clear resin to reduce intensity or saturation. With a catalyst to make the painted surface solidify, the colored layer, with its resin component, would be the last one applied to a board.

Prior to painting, contours of the color areas had to be carefully taped. When the taping was removed, a thin ridge sometimes remained and was gently sanded off, producing a uniform high gloss finish. The colors of Wardy boards have held up well, even in boards often ridden. Wardy recalls using the highest quality color resin available, ordered from a company called Thalco in Los Angeles.

Although coloration was done at the customer’s request, a final choice of color and design was made in discussion with Wardy or a member of his crew. In Figs. 43 to 45, the choice was colored rails, with the top of the board matching the bottom. A dominant or a single color was the preference with Figs. 46 to 50.

Fig. 43. 10'3½″, priv. coll.

Fig. 44. 9'2″, priv. coll.

Fig. 45. Collection of Jim Cocores.

Fig. 46. 9'7″, priv. coll.

Fig. 47. 9'7″, priv. coll.

Fig. 48. Collection of Jim Cocores.

Fig. 49. 9'5″, priv. coll.

Fig. 50. 9'6″, Collection of Jim Cocores.

Designs involving colored bands, their sometimes vertical and horizontal interactions, varying stringer sizes, mediums, and arrangements, and drawn lines can be seen with Figs. 51 to 56. The red band crossing on a diagonal in Figs. 57 and 58 is an element sometimes included when the board was to be ridden in competition. Stripes of that type were also used on sports cars and clothing at that time.

Fig. 51. Priv. coll.

Fig. 52. Closer view of 51.

Fig. 53. Back view of 51, July 1965, Laguna Beach, CA.

Fig. 54. Another board at the July 1965 photo shoot.

Fig. 55. Priv. coll.

Fig. 56. Closer view of 55.

Fig. 57. 9'4″, priv. coll.

Fig. 58. View of the tail of 57.

Restoration of surfboards often involves a new application of color whether it is a new color or the original, which experts can often determine even when it is seriously faded. Single ownership and/or documentation is also helpful in the determination of color during restoration. Some boards pictured in this essay and in Appendix B have undergone color restoration. Done well, such work usually does not bother owners. Wardy is accepting of it because, for him and many others, the functionality and shape of a board and its fin always outweigh color in significance and also because excellent color restoration helps to maintain the look of quality of a board and its aesthetic appeal.

Boards for lifeguards, belly boards, and skateboards:

During the early 1960s, Wardy produced wood boards for lifeguards, who often preferred them to regular surfboards to get through the surf faster by paddling. They measured about ten feet long, were finless, and had a clear resin finish, which included light inhibitors because of sun exposure. When Wardy later made the boards in foam, they were lighter and thicker, with an increase in the curve at the nose for a better grip, all to facilitate two people hanging on to the board safely.

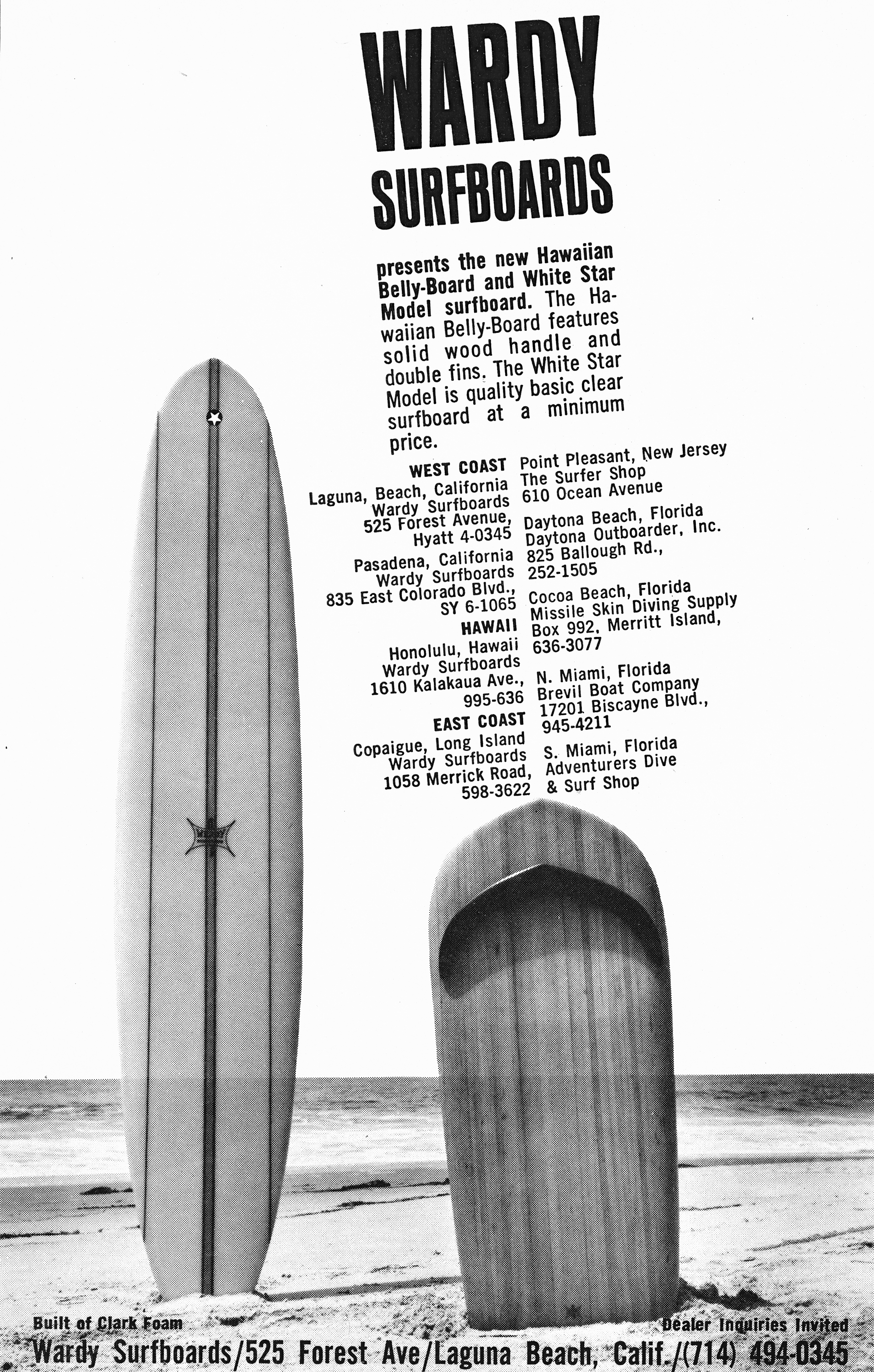

Wardy Surfboards made a small number of belly boards in foam, including those of Figs. 59 to 62. The top of Fig. 61 has the residue of wax that would have been used to prevent the surfer’s feet from slipping. The belly boards were designed for close-in waves although some surfers rode them further out. Usually measuring about three feet in length, they were typically curved up and over at the front, and the rider sometimes wore fins. The boards “were a lot of fun,” Wardy says, noting that they “allowed the rider to move quickly and make lots of twists and turns.” In Figs. 63 and 64, a belly board has a prominent place in an ad in Surfer (Nov. 1965).15

Fig. 59. Belly board, Collection of Jim Cocores .

Fig. 60. Bottom of 59.

Fig. 61. Belly board, Collection of Ryan Frisby.

Fig. 62. Bottom of 61.

Fig. 63. “Wardy Surfboards,” Surfer (Nov. 1965).

Fig. 64. Detail of 63.

The small number of skateboards that were made at Wardy’s shop involved simply the attachment of the metal unit of roller skates to the bottom of a shaped piece of stained wood. Figs. 65 to 67 show one example, including while on view in the 2018 exhibition “Surf2Skate” at the Huntington Beach International Surfing Museum in Huntington Beach, California. Placed next to the balsa board from the Surfing Heritage and Cultural Center, the skateboard is made of Philippine mahogany with forward pointing grain that suits the use of the object.

Figs. 65 to 67. Wardy skateboard, Philippine mahogany, including while on exhibition in 2018.

Although customers often purchased finished boards, requested duplicates of them, or placed an order for something similar, most often boards were custom made at Wardy Surfboards. Consideration was given to where buyers intended to surf, specifically what type of waves they would face, as well as to the customer’s height and surfing ability. Some customers arrived with a list of specifications about color, stringers, etc.; some did not. Although Wardy or experienced crew members worked with customers, the person who often performed this role was Larry Bailey, one of Wardy’s first employees and an outstanding shaper and glasser who stayed with him until he sold his business.

Wardy explained the care given to the ordering of a board in “On Quality Boards. . . . (Surfer, spring 1962):

Proper dimensions for a surfboard are not mysterious to the experienced craftsman. As professional builders, we know the proper size and shape of board each person needs to meet his particular requirements. Its length, width, and thickness, for example, are determined by the weight of the individual.16

Remembering the enthusiasm of his customers during the process of ordering and picking up a board, Wardy has said that “If you liked a board, you didn’t want to switch. It was perfect. You might want to surf all year round.” Fig. 68 is a typical order form (with the customer’s name and address removed for privacy).

Fig. 68. Order form for a Wardy foam board.

Craftsmanship, Quality, Research, and Related Commentaries

In 1963, Petersen’s Yearbook gave Wardy Surfboards a high rating by saying that it “is now considered among the top in quality and quantity” and that it has been popular in “surfing circles for approximately seven and a half years now.” [The writer must have been including the years when Wardy made boards in Highland Park.] The publication pointed out that “Frederick Wardy has built his boards without the use of gimmicks in shape or color to draw attention to his product.”17

In the previous year, 1962, Wardy’s lengthy discussion in “On Quality Boards....” had stressed important aspects of quality and had criticized gimmicks:

A quality surfboard is designed to insure the best possible performance under any and all conditions. Expert craftsmanship is combined with the finest materials available to produce a finished board which is notably beautiful, but also practical, and durable. It is free from so-called ‘gimmicks,’ or unusual but useless features which are employed merely to attract attention to the product, not to fulfill the surfer’s needs.

In the same ad, he refers to the characteristics and practices leading to quality and to achieving perfection:

What makes a quality surfboard? . . . Creative skill and meticulous attention to every detail. Hours of research and experimentation are spent in finding the precise fusion of each component. A quality surfboard cannot be mass-produced, but must be created, step by step, by professionals whose ultimate aid is to achieve perfection.18

Quantity was important, but it always came after quality and is rarely referenced. He did hire more employees over time as orders increased but not many more than he had in 1962.

Two years after Wardy created the “On Quality” ad, perfection is a keynote of the “Wardy Surfboards” ad (Surfer, July 1964), in which Wardy criticizes the idea of a surfboard as a toy and embraces the subject of “perfecting every detail.” He names some of the elements of surfboard making that he rejects and describes what the beauty of a board is all about:

When you purchase one of our boards, you own more than a brightly colored toy—you own a specialized tool which is built for those who desire maximum performance in wave riding. We’re fussy to the point of being old fashioned about perfecting every detail in the construction of our product—and our ultimate aim is to satisfy each individual customer. Our reputations rests on this.

When you come to one of our shops, you’ll notice a lack of the usual array of surfing ornaments and fancy, multi-colored boards. Instead, you’ll see beauty of symmetry, balance, line and form in every surfboard, whether it be balsa wood or foam. We still build balsa boards for customers who prefer them. Their construction requires the skill and patience of the true craftsman. But, we are professional surfboard builders—not toymakers.19

In 2022, Randy Rarick, a widely respected surf historian and restoration specialist based in Oahu, offered his perspective on Wardy boards regarding quality versus ornament:

Since I was one of the repair guys at Surf Line Hawaii, I had the opportunity to repair thousands of surfboards and invariably a number of Wardy’s came into the shop for repairs. I was always impressed as to what clean glass-jobs they had and the cool stringers. Whereas a lot of the other brands relied on colors, radical fins and other gimmicks, the Wardy’s were always very understated and conservative. They let the shapes and quality of the glass work do the talking for them. Subsequently, you see a lot of “clear” Wardy’s.20

In Petersen’s Yearbook No. 2 (1965), in the “WARDY” section of “All About Surfboards,” Dick Graham, referenced earlier, emphasized that the methods of production had not changed at Wardy Surfboards even though demand and production had increased:

Although operating on a much larger scale than in the early days, Wardy and his competent staff still devote maximum effort to the most minute detail in connection with each individual surfboard. Surfing has grown tremendously since then, and the industry has grown with it, but a Wardy surfboard is still “custom-built” board made by skilled craftsmen….

A related part of the piece reads: “Each board carries a guarantee against breakage, and is designed for maximum performance, speed and maneuverability in all types of surf—special shapes being available to follow individual requirements at no extra cost.”21

While visiting Wardy in Long Beach (Fig. 69) in 2022, Rarick discussed the “high quality of the materials used” in Wardy’s boards and how they “have held up very well.” He noted that “the glass work is amazing, and the double glassing technique added to the strength of the boards.”22 In the written comments from 2022 quoted in part above, Rarick addressed his experience in working with Wardy boards:

Fast forward fifty-five years later and when it comes to full restorations of Wardy’s, they are one of my favorite boards to work on. The quality of the glass work means they held up really well. They have a unique swept-back fin template or the even more unique “reverse” fin template. Black only logo and as mentioned, lack of color work makes them an easy board to work on. To date, I have probably restored a few dozen Wardys and all have been exquisite.23

Fig. 69. Wardy with Randy Rarick, Long Beach, CA, 2022.

Greg Noll, a well-known surfer and surfboard maker, gave his old friend Lance Conragan his opinion of Wardy’s work in 2007. Conragan described their conversation in a 2012 blog entry: Noll had been “thumbing through Drew Kampion’s Greg Noll: The Art of the Surfboard (2007)” and then “dished on surfboards and his decades in the industry in general.” When Conragan asked him about Wardy, he replied: “‘Wardy was more than a surfboard shaper, he was a friggin artist, his boards were perfect! And he was the nicest damn guy you could ever meet.’”24

Gerry Lopez, well-known as a surfer, surfboard maker, and writer about surfing, entered the following in his internet blog “Our Surfboards Then & Yet Becoming” in 2014:

Wardy was a classic old style surfboard builder, instilling his own high quality work ethic in all who worked for him. Every board was a masterpiece of perfection in every stage. The building process began with the shape, then progressed to the finely detailed wood tail blocks and fins, beautiful and clean laminations, and the buffed high gloss finish. Although he didn't know me, Fred Wardy had the same effect on me as he did on his employees. His finely crafted boards gave me a standard of surfboard quality to aspire toward when I began to build my own boards.25

Jim Cocores, who established the Thalia Surf Shop in Laguna Beach in 1995 (the shop now owned by his son, Nick), has been a major collector of surfboards for more than forty years and has owned a number of Wardys, as he still does. (See Figs. 15, 45, 48, and 50, and Appendix B for other views of these boards.) In Conragan’s article in The Surfer’s Journal (June/July 2023), Fig. 50 (viewed from the front and back) and Fig. 45 are among boards selected by the magazine for illustration.

The following summarizes Cocores’s admiration of Wardy Surfboards and its advertising:

I’ve owned many surfboards and since I began collecting in the 1980s, and Wardy Surfboards is the only surfboard company I've been partial to. I also love the advertising images of Wardy Surfboards and have collected some of them, including those I displayed as a group at the Thalia Surf Shop.26

Figs. 70 and 71 show (left to right) Cocores, Wardy, Nick Cocores, and (opposite) Graeme Brown, Wardy’s son-in-law, discussing surfboards in Long Beach in 2022. On the grass is a Wardy board newly restored by Rarick for a private collector and a Wardy balsa board (in this essay at Fig. 15) owned by Cocores. Among the other photographs that Cocores has made available is Fig. 72, showing his green Wardy board leaning against another highly regarded object he owns, his 1950 Ford Woodi station wagon. Even with a fifteen-year age difference, some might say that the two possessions seem compatible.

Fig. 70. Wardy with Jim Cocores, his son, Nick Cocores, and Wardy’s son-in-law, Graeme Brown, in Long Beach, CA, 2022; Fig. 71, with a blue and white board and a balsa board, the latter from the Collection of Jim Cocores; Fig. 72, Wardy board (also Fig. 45) leaning on Jim Cocores’s 1950 Ford “Woodi” station wagon. Collection of Jim Cocores.

In preparing to write his article on Wardy, Conragan commented that Wardy “not being satisfied with the status quo . . . wanted to find ways to improve board building.” With seeming ease, he went on to give a knowing overview of Wardy’s surfboard making:

Wardy was just plain interested in learning how to make things and how things work. He tinkered to find out what made a difference in shaping for speed and for different sizes of waves. Not only did he take the initiative to teach himself how to make boards, he developed new ways of making them and taught many others who went on to own their own shops or work for others. It was hard work, and he became one of the best. His longboards gave scope to his ingenuity and creative energy, his sense of both sculptural and graphic design, his engineering skill, and his perseverance and openness to experimenting with and mastering new mediums. Money does not seem to have been Wardy’s primary motivation as much as a love of experimenting and making things and the pleasure of the process.27

On reading this, Wardy responded: “It was a glorious time.”

Petersen’s Yearbook No. 2 (1965) noted that:

. . . not satisfied that a better board cannot be built in the future, Wardy and his staff members maintain a research and development program in which new materials, techniques and theories are constantly being tested.28

See Appendix C for a collection of the commentaries quoted in this section.

When Ron Sizemore was preparing to compete in the 1961 West Coast Surfing Championship at Huntington Beach, Wardy visited the beach and then made a board suitable for the waves. “Because the older pier was there then, the waves broke differently than now,” he recalls, so he “studied them carefully to make a board that would work for Sizemore.” He made the nose of the board (the spot one foot back from its front end) 17¼” in contrast to the normal 16” or less there. The tail was a pintail (a narrowed back end), which was better for riding big waves than more rounded tails. Fig. 73 captures Sizemore at the pier’s pilings during the competition, riding backwards. He took first place.

Fig. 73. Ron Sizemore, West Coast Surfing Championship, Huntington Beach Pier, 1961. Collection of Ron Sizemore.

Although Wardy never accepted trade-ins to lower the price of a new Wardy board, he did pay small amounts for old boards, made by others, when a customer placed an order. He rode these for the sake of research and remembers that one of them hummed because the fin was too squared at its back and vibrated.

Wardy has said that his surfing experiences helped to inspire him in board design and improvement, in writing about surfing, and in giving advice to other surfers. He surfed whenever possible through all kinds of weather and wave conditions. With his crew, he was alert to good wave conditions, especially after hours of sanding boards and being covered in fiberglass and foam dust. Wardy might look at the tide schedule and say, “surf’s up.” Everyone would head out, most often to nearby Rock Pile at the north end of Main Beach and to Irvine Cove further north. Sometimes, they would go down to Trestles Beach, in the northern most part of San Onofre State Beach, which was considered by many to be the best surfing spot in Southern California.

Wardys frequently surfed on large waves, including during trips to his shop in Honolulu. Fig. 74 shows him diving from one of his longboards, probably at Sunset Beach or at Waimea Bay. At the town of Dana Point, on the ocean side of the high cliffs of Cook’s Point, Wardy and others rode waves generated by a notorious surf break called “Killer Dana,” which could surge to more than fifteen feet. Even smaller waves at that spot might slam surfers into the cliff wall of the ocean or harbor side of the point rather than let them pass around it into the harbor.

Fig. 74. Wardy diving from one of his longboards in Hawaii. Collection of Frederick Wardy.

Other extreme experiences included one on a cold and hailing winter’s day at a deserted and desolate Rincon Beach (adjacent to the Ventura and Santa Barbara County line). “Stupidly, “he says now, “I held my surfboard over my head, and only wearing a pair of trunks went into the icy water.” On another day, thinking he was alone at an illegal surfing spot along Camp Pendleton, the Marine Corps base, he took off on a large wave and almost collided with his friend John Severson, the editor of Surfer. He remembers the location well: “It was a fantastic stretch of beach, the place had magnificent waves. On the other hand you had to put up with the Marines.” Camp guards sometimes fired blanks at surfers or, as Wardy experienced, let the air out of their tires. He still maintains, though, “You had no choice, it was the best place to surf.”

Among Wardy’s other favorite surfing spots in Southern California were Doheny State Beach in Dana Point and its neighbor Poche Beach, where he was likely sitting in Fig. 75. The silver bracelet on his left wrist carried his name in case he drowned while surfing. “Silly,” he now thinks looking back at it. He appreciated Doheny: “Even if the waves were small, you could still practice paddling and getting into a wave. It’s the same process at one foot and six feet, even with a fifteen-foot wave, the same thing, paddling and trying to make a turn.”

Fig. 75. Wardy, probably at Poche Beach, Dana Point, CA.

Laguna Beach Shop

The shop, seen in a black and white photograph (Fig. 1), was red, its color captured well in a watercolor (Fig. 76) owned by Sizemore and painted by Lisa Kasprzycki, an artist who was born in Laguna Beach and lived there when young.29 The address of 525 Forest Avenue was not far from the beach and to the right of a water runoff channel and the entrance to Laguna Canyon. To the right of the shop stood, as they still do, the Laguna Beach City Hall and the Downtown Fire Station. When orders grew, some of the glassing of boards was done in an auxiliary shop in the canyon. Today there is a large parking lot at the former location of the shop (Fig. 77).

Fig. 76. Wardy Surfboard shop in Laguna Beach, CA, watercolor by Lisa Krasprzycki, 25½″ x 35½″. Collection of Ron Sizemore.

Fig. 77. The location of the former Wardy Surfboards shop, photographed in 2023.

Wardy was a constant presence in his shop, where this photograph of him was taken (Fig. 78). He is wearing a Wardy Surfboards T-shirt, the kind he gave to customers. The collage of surfing images behind him in the upper right was in the front area of the shop and may have been by Severson. Taken in 1963, Fig. 79 shows Wardy at a rack of foam boards and is from a series on surfboard builders by LeRoy Grannis (1917–2011), a well-known photographer in the Southern California surfing world.30

Fig. 78. Wardy in his shop in Laguna Beach.

Fig. 79. Wardy at a rack of Wardy boards in his Laguna Beach shop, photograph by LeRoy Grannis, 1963.

Fig. 80 captures Wardy shaping the tail of a foam surfboard with a plane in one of the work areas out of sight from the front desk. It appeared in an article entitled “Personalities” in Surfer (Feb./March 1964), which also discussed Bing Copeland and Dewey Weber, both surfers and surfboard makers.31 A detail (Fig. 81) from a Wardy ad, “The Great Assemblage of Power,” in Surfer (July 1965) gives a wider view of Wardy at work adjusting a plane, while another detail from the same ad pictures Bob Machado working on the tail of a board in some way related to glassing. (Fig. 82).32 Petersen’s Yearbook No. 2 called Machado “one of the industry’s top glassers.”33

Customers were curious about the work being done in the back area of the shop. Wardy has said that children used to go around to the back of the building to look through the windows there and would sometimes talk with crew members.

Fig. 80. Photograph of Wardy in “Personalities,” Surfer (Feb–March 1964).

Fig. 81. Detail picturing Wardy at work in his shop in Laguna Beach, in “The Great Assemblage of Power,” Surfer (July 1965).

Fig. 82. Detail picturing Bob Machado at work, “The Great Assemblage of Power,” Surfer (July 1965).

Wardy described the shop this way in Fig. 83 (Surfer, Dec. 1962/Jan. [1963]):

Once upon a time, not really too long ago, a surfboard shop was a very unique, ‘special kind of place’—a shop at the beach where the surfer could meet his friends to exchange ideas and theories on surfing, waves, and boards. He could order his new surfboard to his exact specifications and even watch many of the steps being performed. This era has since passed, and due to the increased popularity of surfing and its influx of followers, there remains only one surfboard shop of this kind on the Pacific coast. It is an unobtrusive, red barn of a building situated between the mountains and the sea on a quiet street in the town of Laguna Beach. The white sign atop its roof spells out WARDY SURFBOARDS.

As one walks through the front door of this antiquated looking building, he is certainly not impressed by garishness of color nor ostentation in any form. There is no ornamentation, no trinkets or miscellany to buy. There are only fine surfboards. The newcomer might very well be disappointed in the small display room and its obvious lack of adornment. Yet for the surfer, it is enough—he knows that beyond the glass-windowed door, the most excellent methods and techniques are applied in constructing one of the very best surfboards attainable.

Within the confines of this small shop, a surfboard is created, step by step---from the thinking stages through the designing and shaping to the laminating, sanding, glossing and polishing. Unlike most modern-day shops who ‘send out’ a good deal of their work to others on contract, every detail, no matter how minute, is attended to within our shop by our own skilled, experienced craftsmen. They offer you their best.34

The shop appears as a small-scale black silhouette against a much larger white background with the witty words “we’re small in a big way” (Fig. 84) (Surfer, Nov. 1964).35 Surf Culture: The Art History of Surfing (2002), mentioned earlier, reproduced the ad on a full page.36

Fig. 83. “Wardy Surfboards,” Surfer (Dec.1962–Jan. 1963).

Fig. 84. “we’re small in a big way,” Surfer (Nov. 1964).

David Christakes, who grew up in Laguna Nigel and lived in Dana Point for many years, sketched the Wardy Surfboards shop in pencil as a teenager about 1966 and later used the sketch as the basis for a pen and ink drawing, which in turn became the source for his 1979 watercolor (Fig. 85, 11″ x 14″). Christakes says that the watercolor “is a bit dramatic” because of his interest in shadows at the time. A reproduction of it now hangs in Turk’s Restaurant in Dana Point while the original is in his tiki bar at his residence on Orchid Island, Florida. Fig. 86 is one of the small cards he had made from this work.37

About 1992, Christakes painted a second watercolor with several fancifully invented details, including a palm tree, a drop box for surfing movies, and a sign with a large Wardy logo. In the distance and now looking a tad like a castle tower is a version of a sewage treatment unit. He also enlarged the window area with boards standing on end rather than placed horizontally. The watercolor was reproduced, as in the case of Fig. 87 (11″ x 17″), by offset lithography and was originally intended to comprise a run of four hundred. This work was followed by a Christmas card (Fig. 88) from an original in watercolor with Santa and his sleigh in the night sky. It is part of a series by Christakes depicting surfboard shops and surfing establishments, including Hobie’s in Dana Point, Del Cannon’s in San Clemente, the Greek’s in Huntington Beach, and Russell’s in Newport Beach. While living in Dana Point, Christakes was actively involved with clean sea water and beach access issues for many years and continues to take an interest in ocean related matters now that he lives in Florida.

Fig. 85. Wardy Surfboards shop, watercolor by David Christakes, 11″ x 14″. Collection of David Christakes.

Fig. 86. Wardy Surfboards shop, by David Christakes, 3⅞″ x 5⅛″. Collection of Frederick Wardy.

Fig. 87. Wardy Surfboards shop, offset print (no. 7 of a planned run of 400), from a watercolor by David Christakes, 11″ x 17″. Collection of Frederick Wardy.

Fig. 88. Christmas card, watercolor by David Christakes. Collection David Christakes.

Wardy Surfboards sold nothing other than surfboards for several years, observing in “A Few Words on Surfboards,” an ad in Surfer (Dec. 1963/Jan. [1964]: “We don't sell the usual accessories and paraphernalia, such as trunks, photographs, etc.”38 Eventually, its practice changed, however modestly. In one of his commentaries (“Ask the Expert by Corky Carroll”), the well-known surfer and writer on surfing Carroll responded to a question about Wardy’s custom-made surf trunks with the information that they were made by Mrs. Barney Wilkes, “the wife of surf legend Barney Wilkes and the mother of hot surfer John Wilkes.” He added: “Both Fred and Mrs. Wilkes made good stuff and are definitely surfing historical.”39

Other Wardy Shops

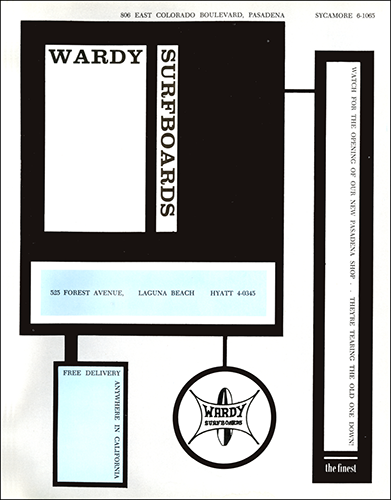

Pasadena:

Wardy’s other outlets helped to bring his boards to the attention of surfers living inland from the Southern California coast. His first Pasadena shop at 806 Colorado Boulevard, a main drag, opened in 1959, soon after he set up production in Laguna Beach. With a low rent because the building was to be demolished in the fall of 1963, the shop was spacious and windowed and thereby allowed for displays of boards on racks. Wardy recollects that many people in Pasadena and the area were interested in surfboards and that the shop’s first sales occurred “almost immediately.”

Surfing Yearbook (1963) by Petersen’s commented that, “The Wardy Shop at 806 East Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena has become as known to San Fernando Valleyites as his shop in Laguna is to the beach community.”40 Many surfers remember it and its successor in Pasadena well, in part because they bought their first boards there.

When the demolition occurred during or soon after the winter of 1964, Wardy moved across the street to 835 East Colorado Boulevard, a small, windowless building on an alley behind the buildings facing Colorado that was a popular spot with various businesses, including a See’s Candies store. Wardy’s place was small but filled with boards standing vertically to save space. He decorated it with palm branches above the boards.

The following are some of Cocores’s memories of the second Wardy shop:

When I grew up in Alhambra [about eight miles east of Los Angeles and about five miles from Pasadena], there were not a lot of surf shops around. A good friend of mine and my cousin John and I used to visit the Wardy shop in Pasadena. We learned a lot about surfboards on each trip. We saved our money, and then the three of us went to the Wardy shop and we each ordered a custom Wardy surfboard. Mine was a beach break model.41

Honolulu:

Wardy’s shop in Honolulu at 1610 Kalakauá Avenue, about two miles from Waikiki Beach, appeared in a photograph in a local newspaper, probably around 1965 (Fig. 89). The window shows Wardy longboards and some belly boards. The shop was run by John Thurston, one of Wardy’s former shapers in Laguna Beach. Gerry Lopez, who grew up in Honolulu, wrote about it online in 2014:

John Thurston's Wardy shop was different. Right away [Thurston] welcomed us and didn’t mind us hanging around after school. Every day we would show up, touch all the boards, ask a million questions and wish we could own one of the gleaming beauties.42

Fig. 89. Wardy Surfboards shop, 1610 Kalakaua Avenue, Honolulu, ca. 1965.

In 2022, Lopez reflected on his experience with Wardy boards at the Honolulu shop:

It was no surprise when I heard that Wardy moved to NYC and became a successful artist. I was only fourteen years old when I became familiar with his work. John Thurston moved to Honolulu to open a Wardy Surfboards shop on Kalakaua Avenue around 1963, just down the street from my high school. The boards on the rack were each unique masterpieces of perfection in every stage from blank, shape, glass job, finish work, everything. . . . I owned a beautiful light green tint, 3” redwood stringer beauty in my sophomore and junior years. All the boards in that shop were finely crafted works of art that gave me a standard of quality to aspire towards when I began to build my own boards and especially when Jack Shipley and I started our Lightning Bolt surf shop.43

Randy Rarick recalled in 2022 his visit to the same shop:

I had the pleasure of visiting the Wardy dealership in Honolulu in the mid-60’s. John Thurston was the manager, and the shop was located on the mauka end of Kalakaua Avenue at the start of Waikiki. At that time, there were only two manufactures locally, being Surfboards Hawaii and Inter-Island Surf Shop, which then became Surfboards Makaha. So, the mainland manufactures had dealerships, with Surf Line Hawaii carrying eight different mainland brands and Hobie and Greg Noll being represented by stand-alone dealerships. So it was a big deal when Wardy opened up a shop.

I remember a very young Gerry Lopez rode Wardy’s and also Roy Metzger, who was one of the hot guys in the mid-60’s.44

San Francisco;

For a time, Wardy had a shop at 1333 Columbus Avenue and Beach Street, near Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco. An ad in Surfer (July 1964) referred to it as being new. Other shops also carried Wardy boards about this time, including the Bamboo Reef Dive Shop, run by Al Giddings, where Conragan bought his first custom surfboard, a Wardy, in the early summer of 1964. The following by Conragan is from a 2017 longboard blog:

The board was magic, and really helped me up my game. Of all the longboards I ever owned back in the day, which included a Weber Performer, Bing Lightweight, Trestle Special, Hansen Master, and a couple other gems, the Wardy is the one I wish I still had today.45

Elaborating on those comments the same year, he dwelt on the board’s characteristics and repeated his wish to have it today:

I had saved my lawn cutting $ for over a year, folks kicked in, and I agonized for a month before placing the order: 9’8” clear, T-band center stringer with 1/8” outside stringers, two thin diagonal racing pinlines, 7-piece tailblock, and a first-generation speed skeg.

When the board finally arrived after a several months wait and I paddled it out for the first time, it instantly became the best board I had ever ridden. Superbly balanced, ‘neutral’ handling, easy turning and fast down the line. That board created a lot of memories over the next few years including for the transplanted Hawaiian gal who needed a board and became my girlfriend . . . she liked the board that much . . . lol.

Over the decades, I surfed, travelled the world extensively, ordered well over a hundred custom boards from some fine shapers including some of the ‘big names’—and if I could have a single board from my past, it would be that Wardy.46

Long Island, New York (and sales at other locations):

For a short time, Wardy had a shop in Copiague, Long Island, a hamlet on the south shore, about thirty-five miles east of Manhattan. He had gone to Long Island with Frank Robertson, one of his employees from Laguna Beach, to scout the area, including Montauk, for a good shop location.

Central Skin Divers, which called itself “one of the largest distributors of Surf Boards on the East Coast,” was in Jamaica, Long Island, twenty-four miles from Copiague. Its October 1966 brochure (Fig. 90) had as its inside front cover (Fig. 91) information on ordering a Wardy surfboard or one by Con Surfboards (CON), also in California. The companies are described as “FAMOUS BRANDS,” and they (and another company) are said to have been “found to be excellent.” A decal section of the brochure includes a Wardy logo decal.47

Wardy boards were sold in retail shops run by other owners, not only in San Francisco as noted but also in Point Pleasant, New Jersey, and in Daytona Beach, Cocoa Beach, North Miami, and South Miami, Florida.

Fig. 90. Central’s Surfin’ Catalog cover, mailing date of Oct. 1966, from Jamaica, NY.

Fig. 91. Inside cover of Fig. 90 with information on ordering a Wardy board.

Posters:

Wardy designed two types of small posters for his shops. Fig. 92, for Copiague, represents one of these and was also used for his Laguna Beach, Pasadena, and San Francisco shops. Fig. 93 is the poster type used as well for Laguna Beach, Pasadena, and possibly other locations. The surfer pictured is Wardy, who remembers the location as being Trestles Beach, mentioned earlier as a favorite of many surfers.

Fig. 92. Poster type used by Wardy Surfboards for several locations, including Copiague, Long Island.

Fig. 93. Another Wardy Surfboards poster type, here with the locations of Laguna Beach and Pasadena.

Logo and business card:

Wardy’s first business card was a plain, printed one (Fig. 94). Subsequently, his business card and stationery featured an incisively drawn, fun-loving and big-footed surfer with a board under his right arm, running as if toward a shoreline (Fig. 95). Wardy believes that this figure was drawn by John Severson. The surfer resembles caricatural figures with large feet created by two well-known caricaturists working in Southern California at the time, Rick Griffin and Severson.48

Fig. 94. An early business card, probably 1959.

Fig. 95. Definitive business card, probably designed by John Severson in 1960.

Wardy used a hand-sketched, diamond-shaped horizontal logo (Fig. 96) on some of his early boards but soon designed the easily recognizable Wardy Surfboards logo (Fig. 97). Occasionally a surfer might request that his board carry the linear elements of one of his poster types as seen in seen in Fig. 98.

The logo is noteworthy for its clarity, derived from the curving movement of lines extending outward to four points and from the strong presence of a vertical board with black and white converging diagonal elements. Wardy’s careful choice of typeface and size added to the logo’s impact. Its appearance varied according to the item on which it was placed: on patches (Figs. 99 and 100), shirts (Figs. 101 and 102), larger ones from the back of shirts), and in certain ads, such as Fig. 103 (SoCal Surfing News, Feb. 1963), where it has an extra outline as it takes up half a page.49 Sizemore sometimes wore trunks onto which a large logo from the back of a shirt had been sewn. His trunks advertised Wardy boards not only while he was on the beach but also every time he got onto a surfboard. The ploy was eye-catching, humorous, and a good public relations job for him because surfers could see him in action and they knew how good he was.

Wardy’s logo stood out when shown with others, as can be seen in Fig. 104, a striking inside back cover ad by Clark Foam (Surfer, Oct.–Nov. 1963).50 The price list brochure containing Wardy’s essay “On Quality Surfboards” (Figs. 105 and 106) carried his logo. The logo is currently registered to an owner who has no connection with Wardy boards, as Wardy inadvertently and unfortunately let his rights to it expire some years ago.

Fig. 96. Early diamond-shaped logo from a Wardy board.

Fig. 97. Definitive logo on a Wardy surfboard, from Fig. 19.

Fig. 98. Unique logo, related to the poster type of Fig. 91. Courtesy of Erwin Spitz.

99. Patch with the Wardy logo, 3″ diameter

Fig. 100. Patch with the Wardy logo, 3″ diameter.

Fig. 101. Back view of a Wardy T-shirt. Collection of Frederick Wardy.

Fig. 102. Back view of a Wardy T-shirt, with “HAWAII” included. Collection of Frederick Wardy.

Fig. 103. SoCal Surfing News (Feb. 1963).

Fig. 104. Surfer (Oct.–Nov. 1963), Wardy logo within a Clark Foam ad.

Fig. 105. Front cover of the Wardy Surfboards price list.

Fig. 106. Inside view of the Wardy Surfboards price list.

Sponsorships and advice to young surfers:

When surf clubs were formed in the early 1960s as part of the increasing interest in surfing, Wardy Surfboards sponsored some of them, including the Midway Surf Club in Pasadena. Although Wardy never took returns as payment toward a new board, Carl Abejon, a surfer from the Midway club, recalls that there seemed to be an exception for club members. He returned many boards, not because of problems with them but because of his eagerness to try another Wardy. He would get “new ones for very little,” he says.51

Surfing Yearbook (1963) by Petersen’s reported Wardy’s advice to young surfers in an article entitled “Interview with the Greats,” in the “FREDERICK WARDY” section. It points out that “Wardy feels that while surfing is one of the greatest individual sports, it shouldn’t be the only sport or interest in the lives of some of the younger surfers. . . .” Supporting the point is the mention that “Reading good books” and “dabbing with a paint brush” are among activities that help to keep Wardy busy.” The piece then quotes Wardy:

‘Don’t let the sport dominate your life. Be careful not to use surfing just for status or recognition. Keep your life in balance and go surfing for the pure enjoyment of the sport.’52

“Personalities” in Surfer (Feb./March 1964) noted that “Wardy enjoys surfing purely as a sport” and quoted his advice to young surfers:

‘Surfing can get out of perspective. Some kids think it is a complete way of life. They should take it like any other sport—surf, then go do the other things important for a full life.’53

Selections of Wardy’s Advertising Imagery and Writings

Wardy’s writings about surfing were a major part of his magazine advertising, as earlier quotations indicate. These writings explain at length what goes into making surfboards and provide a great deal of other information about the experience of surfing. In doing so, they demonstrate a commitment to educating the public about these subjects.

Wardy’s advertising appeared mainly in Surfer magazine, which began publication in Laguna Beach in January 1960 under its founder and editor, John Severson. Wardy also advertised in the short-lived magazines Reef in 1960 and in both SI Surfing Illustrated and SoCal Surfing News in 1963.

The Wardy Surfboards ads stand out not only for the excellence of their writing but also for their originality, variety, and design quality. Wardy’s first ad featured the happy surfer on his business card (Fig. 107) and appeared in Surfer’s first issue.54 The same running figure, boldly defined in white against black (Fig. 108), surfaces in Reef (Aug. 1960).55

Fig. 107. Wardy business card, Surfer (Jan. 1960),

Fig. 108. “WARDY SURFBOARDS,” Reef (Aug. 1960).

“Discriminating People Use Wardy Surfboards” (Fig. 109) (Surfer, fall 1961) depicts gleeful, tousled-haired surfers drawn by Wardy running waterward with their boards, evoking the figure on his business card. The ad was well placed, taking up one half of an inside front cover.56

Fig. 109. “Discriminating People Use Wardy Surfboards,” Surfer (fall 1961).

Longer ads include two consisting chiefly of writing. “On Quality Boards. . . .” (Surfer, spring 1962) (Fig. 110), with its descriptions of the elements of and workmanship required for the creation of a quality surfboard, was quoted previously.57 [The ad shown as Fig. 6, “The Emblem and the Craftsmen,” appeared in Surfer in the 1962 May/June issue.] “Confidence,” in SI Surfing Illustrated (spring 1963) (Fig. 111) and Surfer (Aug.–Sept. 1963) (Fig. 112), discusses the characteristics of a board that give it exceptional performance.58 The bottom of Fig. 112 holds a logo and a notice that Wardy Surfboards also makes balsa boards, in other words, was still making them even though foam boards had held sway for some time

Fig. 110. “On Quality Boards….,” Surfer (spring 1962).

Fig. 111 and 112. “Confidence . . .,” SI Surfing Illustrated (spring 1963).

Among Wardy’s ads with strong design qualities, Fig. 113 occupied a full page on an inside back cover of SI Surfing Illustrated (fall 1963).59 In its use of rectangles of single colors, it evokes geometric abstraction in twentieth century art. The prominent, eye-catching printed information included the reference to a new Pasadena shop, replacing the one established in 1960, and to a business practice: “FREE DELIVERY ANYWHERE IN CALIFORNIA.” Wardy says that this was a special offer made prior to Christmas, when many customers bought boards, and that he personally made deliveries within reasonable driving distances in his Volkswagen van.

Fig. 113. SI Surfing Illustrated (fall 1963).

Quoted from earlier, “A Few Words on Surfboards” (Fig. 114) in Surfer (Dec. 1963 to Jan. 1964) appears here chronologically and is a good example of the effectiveness of a print ad, in this case, with a particularly light, conversational quality:

We use this excellent quality foam because—well, because his shop [Clark Foam Products] is just down the street from us. . . . We also make a lot of balsa wood boards—much to the agony of our shapers. . . . we hope you’re interested enough to find time to visit our shop in Laguna. Better yet, we hope you’ll find our shop—it’s rather uncentrally located on a back street. . . .60

Fig. 114. “A Few Words on Surfboards . . .,” Surfer (Dec. 1963–Jan. 1964).

A strong sense of merging with nature characterizes the text and photograph of Fig. 115, which covered a full page in Surfer (Feb.–March 1964). Wardy, recognizable to many but unnamed and with his back to the viewer, holds a board under his right arm as he walks along the water’s edge, although one might read the blurring of the sand as water. Wardy’s words describe the experience of moving from the known to the unknown:

From the moment he enters the water the surfer has no other wish, no other thought, but that of catching a wave and riding it—thus becoming one with the sea—a part of a vast unknown and timeless thing.61

Fig. 115. Surfer (Feb.–March 1964), based on a photograph of Wardy.

Shortly after creating this evocative ad, Wardy drew an amusing one (Fig. 116) featuring a bull standing on his hind legs (Surfer, April–May 1964). The caption reads, “Don’t let the bull throw you!,” a reference to the hyping of surfboards in advertising.62 Wardy still owns the preparatory work, a pristine 17″ x 14″ ink drawing of the bull.

Fig. 116. “Don’t let the bull throw you!” Surfer (April–May 1964).

“Wardy Surfboards” (Fig. 117) (Surfer, July 1964), quoted earlier, emphasizes the importance of experience in board building, including the remark that “We’re fussy to the point of being old fashioned.” Small, old-fashioned decorative details and typeface at the top and bottom of the copy underlined the point. Adjacent to the column of copy and as high is a photograph of a surfer holding upright a tall, narrow wood board that tapers radically at the nose and tail, making it obviously antiquated. The ironic caption reads: “Nothing can ever come between me and my old Wardy board.”63 Old fashioned ornamentation frames the photograph, echoing the decoration of the column of print.

Fig. 117. “Wardy Surfboards,” with “Nothing will ever come between me and my old Wardy board.,” Surfer (July 1964).

Wardy’s next ad (Surfer, Sept. 1964) (Fig. 118) has both charm and pleasing aesthetics in its view of a boy with a long stick printing Wardy’s name in large, capital letters in wet sand.64 The boy is Dana Brown, born in 1959 in Dana Point and the older son of one of Wardy’s friends, surfer and filmmaker Bruce Brown, known for his documentary on surfing, The Endless Summer (finished, 1964; released, 1966). Wardy lived near the Brown family at Dana Point, and Brown had recommended the place to him, a small house on a cliff face. Dana has gone to be a writer and a film director.

Fig. 118. “WARDY,” Surfer (Sept. 1964).

Humor is dominant in Fig. 119, which took a full inside back cover of SI Surfing Illustrated (winter 1964). Wardy drew a guitar-playing turtle and a disheveled person in a nightshirt who complains, “I wish Wardy would come and get this ridiculous turtle of his……. Because I haven’t slept since he left him here.” Wardy expected that the silly text would tease the viewer into puzzling over it and hence keep registering Wardy’s name.65

Fig. 119. SI Surfing Illustrated (winter 1964).

Also on a humorous note is “Santa’s on The Stick” (Fig. 120) (Surfer, Dec. 1964/Jan. [1965]). Wearing elves’ boots, Santa rides a broomstick with the Wardy logo. “Stick” functions as a common reference to a surfboard.66

Fig. 120. “SANTA’S ON THE STICK,” Surfer (Dec. 1964–Jan. 1965),

About a year after Wardy created the ad featuring a photograph of himself carrying a board near water (Fig. 115), he based an ink drawing on the image (Fig. 121) for an ad in Surfer (May 1965). The outline of his body is filled with names people in the surfing world, including many surfers and board builders. Beneath the figure are the words:

WARDY SURFBOARDS is not merely the work of one man . . . it is the combined efforts of many. Each of these qualified men has contributed his ideas, opinions, and criticisms toward a common goal—the creation of a better surfboard. And, as we continue to grow and improve, the list of names grows with us. In essence, Wardy Surfboards is people.67

Fig. 121. “Wardy Surfboards,” Surfer (May 1965).

For “The Great Assemblage of Power” (Fig. 122) (Surfer, July 1965), Wardy created an elaborately collaged arrangement of the names and photographs of surfers, board builders, and others associated with surfing as well as puns and jokes. The work is akin to collages large and small then being created in significant numbers in American art. Wardy’s name appears in bold capital letters on cut pieces of paper in the lower right. Photographs include Figs. 80 and 81 of Wardy and Machado as well as ones of Bailey (a shaper at Wardy Surfboards, described here as a “different breed of cat”); Del Cannon on a board; and Severson.68

Fig. 122. “The Great Assemblage of Power,” Surfer (July 1965).

The ads showing beach break boards (Figs. 123 and 124) mentioned in the discussion of foam boards date chronologically to this point (Surfer, July 1966; Sept. 1966). Del Cannon was a good choice to be the rider considering his outstanding reputation as a surfer.69

Fig. 123. “Wardy Beachbreak Board for Small Waves,” Surfer (July 1966).

Fig. 124. “Wardy Beachbreak Board for Small Waves,” Surfer (Sept. 1966).

To view the advertising above in chronological order, please see Appendix E. For the advertising copy only, consult Appendix D.

Wardy’s Essays: “The Lure of the Sea” and “Surfing Is”

In Surfer (July 1964), a column entitled “Surf Bill” focused on Wardy (Fig. 125), among four others in the surfing world and had words of appreciation for Wardy’s essay “The Lure of the Sea” and its accompanying photography by Severson.

In this edition we touch on many surfing areas of the world, which points out to us that surfing is still spreading like wildfire. It pentrates [sic] the culture and changes the customs wherever it touches. It seems to be more than a sport; it’s a way of life and its attraction is portrayed by Fred Wardy in a beautifully written piece called The Lure of The Sea. Its message is universal and is certain to be remembered by surfers for a long time to come. John Severson’s beautiful wave photography appropriately accompanies the moving piece.70

Fig. 125. Photograph of Wardy, “Surf Bill,” Surfer (July 1964).

After appearing in Surfer, “The Lure of the Sea” (Figs. 126 and 127) became widely known. In it, Wardy conveys the emotional experience of surfing, including the sea’s power and the deep connection with it felt by surfers. Part of the first paragraph describes “the eternal sea”:

. . . its greatest fascination lies in the huge, pounding waves which constantly hurl themselves from its glistening surface. Crashing violently, the angry surf spills its wrath upon the land, as the two merge in chaotic splendor. The haunting wind wails as it sweeps across the surging waves. As if suddenly aroused from a deep slumber, the sea rears in untamed fury—driven by the relentless wind and hounded forever by its raging breath. The roaring surf cries aloud, as the water below moans—and the vast ocean floor quakes and trembles.

In the second paragraph, Wardy writes that the surfer’s “senses are alive in the pulse of the sea as it beats a melancholy rhythm on the sands—ebbing and flowing in endless motion.” The final sentences of the essay read:

In its transit moods of serenity and rage, peacefulness and violence, it [the sea] reminds man that his time on this earth is not long enough to be filled with war and hate, anger and malice. Standing before the vast expanse of ocean, his cares are forgotten and his restless spirit quieted. His soul is cleansed by the perpetual movement of the sea—the waves.71

Appendix F holds the full essay.

Fig. 126. “The Lure of the Sea” by Frederick Wardy, Surfer (July 1964),

Fig. 127. “The Lure of the Sea,” Surfer (July 1964), continued.

Less than a year after the appearance of “The Lure of the Sea,” Surfer published Wardy’s essay “Surfing Is” (March 1965). The layout opens on the right hand page of a spread (Fig. 128) with Grannis’s full-page color photograph of a sunset over the Pacific Ocean (Fig. 129). The text appears on the following double-page spread (Fig. 130). On the right is a photograph of a rocky beach with a gull in flight and a surfer carrying a board in the middle distance. The photographer, Lee Peterson, is well known today as a nature and wildlife photographer.72

Fig. 128. Surfer (March 1965), spread that includes a photograph by LeRoy Grannis, which introduces “Surfing Is” by Fred Wardy.

Fig. 129. Grannis’s photograph, with added printing.

Fig. 130. “Surfing Is” by Fred Wardy, Surfer (July 1964).

“Surfing Is” focuses on emotion-laden experiences of surfing, with almost all sentences beginning with “Surfing is” or ‘it’s.” Examples include:

Surfing is the joy of watching a sun rise slowly into the sky. It’s crisp, clean waves, crests blown high by an offshore wind. It’s grey mist . . . the lonely cry of a gull sweeping across silent brooding seas. On a big day, surfing is a strong swell and waves that have lost their playfulness.

A paragraph near the end reads in part:

Surfing is . . . a combination of love, knowledge, respect, fear, instinctive perfection gained through repeated contact. . . . a moment of achievement, of glory, of unsung triumph. For the adult, surfing is freedom and youth rediscovered and, for the young, a means of expression vital to their being.73

Appendix F has the full text of this essay.

Severson, who had asked Wardy to write “The Lure of the Sea” and “Surfing Is” for Surfer devoted the first pages of his book Great Surfing to the essays, accompanied by photographs. (The book was published in 1967 by Doubleday & Company.)74

Surfer sometime later published “Surfing Is” as a poster (Fig. 131).75 The essay appeared in The Perfect Day: 40 Years of Surfer Magazine (2003), edited by Sam George. The photograph accompanying it there is by Ron Stoner and shows a surfer entering the water with high breaking waves. The introductory note reads, “Laguna Beach surfboard builder Fred Wardy, known for his quirky, literate advertisements, penned this passionate manifesto for a Surfer photo feature.”76 “Surfing Is” was also reproduced in Surfer Magazine 1960–2020 (2022) by Grant Ellis (published by Rizzoli International). The Grannis photograph precedes the essay on the previous page as it did in Surfer.77

Fig. 131. Surfing Is” poster, published by Surfer, 22″ x 17″. Collection of Frederick Wardy.

The Fly, writing under the name he now used, Jean-Pierre van Swae, showed his appreciation of “Surfing Is” in a 1987 article, “Catch a wave and you’re. . . .,” for the Laguna News Post. He writes that he is “thankful each and every time” he surfs and continues with: “It’s a spiritual experience. On that note, I’d like to share a couple of paragraphs from Frederick Wardy’s article, entitled ‘Surfing Is.’” At the end of the quotation, he adds: “That was written more than 20 years ago. I feel lucky to have Wardy for a friend. Mahalo.”78

To continue with this essay, please click here.