ABOUT WARDY

Overview:

Frederick Julian Wardy (born in 1934) is a prolific abstract painter and sculptor who has worked in many styles and mediums, producing paintings, works on paper, and sculpture. His art career began in the late 1960s and continues to the present. Selections from twenty-nine stylistic categories of his works are arranged in chronological order in Artwork. Miscellaneous works make up a thirtieth group. Informational headings accompany each category.

Wardy’s paintings on canvas and works on paper usually have complex interactions of color or of line and demonstrate an ambitious control of mediums. They reveal a love of color and, in some cases, a fascination with the possibilities of black and white. Wardy’s acrylic and oil paintings on canvas vary in size (from 10″ x 8″ to 8' x 6') as do his works on paper (from 5″ x 3″ to 29″ x 20″). The latter are made with various combinations of gouache, ink, lead or graphite pencil, charcoal, pastels, pastel stick, and oil stick. Wardy has produced sculptures in iron, steel, cut wood, twigs, canvas, and plaster. His sculpture sometimes shows a kinship with examples of his two-dimensional works in the use of linear elements and directional movement.

Wardy established Wardy Surfboards in Laguna Beach in 1959 and made surfboards there from 1959 to 1967. His name and surfboards are part of surfing lore in California and Hawaii. A section of this website is devoted to an essay on Wardy Surfboards illustrated by photographs of surfboards, advertisements, and other visual material related to Wardy, his shops, employees, etc. Substantial additional material can be found in the appendices.

Wardy’s career as an artist began in the late 1960s in Los Angeles and continued in New York City, where he maintained a studio in the Tribeca district of Manhattan for more than thirty-five years. Beginning in the late 1990s, he also maintained a studio on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State. He currently works in Long Beach, California, and in Manhattan and is represented by private art dealers. His work is in various institutional and private collections.

Early years:

Frederick Julian Wardy was born on November 18, 1934, in Los Angeles and was raised by his maternal grandparents in Highland Park, a neighborhood in northeast Los Angeles. The only child in a large, warmhearted, three-generational household, Wardy was given many responsibilities, and work was an integral part of his young life. His work ethic has remained strong to this day.

As a grade˗schooler, Wardy rode his bike to the local Catholic church and parochial school early in the morning. Alone, he turned on the sanctuary lights and lit the candles, then served as an altar boy at Mass with another child. He had breakfast with his teachers, the nuns; classes followed. On weekends, he took a bus by himself to another part of Los Angeles to assist with Saturday and Sunday masses at an affiliated church.

Fig. 1: Wardy with his grandparents, mother, and uncles, 1944.

Wardy interpreted for his Spanish-speaking grandparents from a young age. He also regularly walked two or three miles to and from markets with his grandmother; sometimes he did the shopping alone by bike. When he was in junior high school, Wardy would meet his grandfather, who came home from work late at night, at his trolley stop to walk home with him because the family lived in “a pretty tough neighborhood.”1

Wardy sought out new experiences. During the summer of 1945, when he was ten and visiting relatives in Tijuana, he walked three or four miles most mornings (sometimes jumping through scorpions) to the famous Aqua Caliente racetrack, which attracted the top racehorses and jockeys of the day. Wardy was there watching the morning exercises so often that some of the trainers asked if he would walk their horses after their workouts. He was the only youngster around and worked regularly without pay.2 When his grandfather came to Tijuana that summer, he and Wardy went to bullfights at a nearby stadium. Wardy was spellbound by the mastery of the matadors and has often recalled their “courage in taking risks, really terrible risks” and “the expertise required to master dangerous circumstances.” He remembers seeing the famed Spanish bullfighter Manolete, whom many regarded as one of the greatest bullfighters of all time. Wardy’s experiences that summer at the track and bullfight arena foretold a deep appreciation of courage and expertise that would stay with him.

Fig. 2: Wardy and his mother, Henrietta, ca. 1945, Highland Park, CA.

Wardy’s attraction to the ocean began when he was about ten. He would go with his uncles and grandfather to swim at Long Beach, which then had a curved breakwater of large rocks. He taught himself to swim going from rock to rock. He became a strong swimmer and often bodysurfed at beaches closer to Los Angeles. While in high school, he was taken by a friend to Malibu where he saw surfers in action and knew instantly that he wanted to try the sport. He soon acquired his first board and after being dumped by a large wave in Malibu sought out less challenging surf at beaches near Los Angeles where he could “get the hang of it.”

At twelve, Wardy was again doing something unusual for his age. He had a summer job on weekends driving a truck alone to San Diego where he picked up barrels of tallow for soap and drove them back to Los Angeles. Wardy’s independence, skill, and physical strength had opened him to a new experience, an occurrence frequently repeated.

One summer while in high school, probably about 1950, Wardy pitched without pay for a well-known and successful semi-pro baseball team, the Rosabell Plumbers, a company-sponsored team launched in 1936 and based in Highland Park. He had hung around watching its practice sessions and games, and the team manager asked him if he could pitch. He said he could. Although he had never been on an official team, he had pitched to friends and had slung newspapers to doorsteps from the window of a moving car while on his paper route. A 1947 article in the local paper called the Rosabell Plumbers “one of if not the greatest semi-pro teams in the United States.”3

Fig. 3: Yearbook photograph, 1953, Fig 4: Wardy in Highland Park, Cathedral High School, Los Angeles. 1954.

After graduating from Cathedral High School in Los Angeles in 1953, Wardy studied liberal arts and education at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) thinking he might become a teacher. He interrupted his studies to take advantage of the GI Bill for education and enlisted in the Army in 1955 in the aftermath of the Korean War. During his two-year term of duty, an Army friend, who oversaw recruit training placement and knew of Wardy’s interest in challenges, assigned him to training in driving heavy cargo trucks, parachute landing, and sharp shooting.

Fig. 5: Wardy in the Army when stationed at Fort Lewis in Washington State, 1955.

A lifeguard at an Army pool noticed Wardy’s swimming ability and encouraged him to do rigorous strength training, including swimming with his ankles tied. For a time, he swam the crawl for an Army team. Returning to Highland Park in 1957, he continued with courses at UCLA.

An interest in art had been stirred early in Wardy’s life. When he was twelve, he rode his bicycle to the then small Los Angeles Museum of Art where he came upon many works by Vincent van Gogh. Wardy remembers thinking, “I’d like to do this.”4 Over the next twelve years, Wardy’s attraction to art grew, and in the summer of 1958, he took his first trip to Western Europe to visit art museums. He traveled widely, going to England, France, Italy, Spain, Germany, and Belgium. Wardy sold everything he owned of value, including his car, to pay for the trip, and bused across the United States to New York, taking nothing but what he could carry in his rucksack. He sailed from New York on a Greek freighter, which encountered an enormous storm at sea, “a great experience because of the big waves and swells,” he recalls.

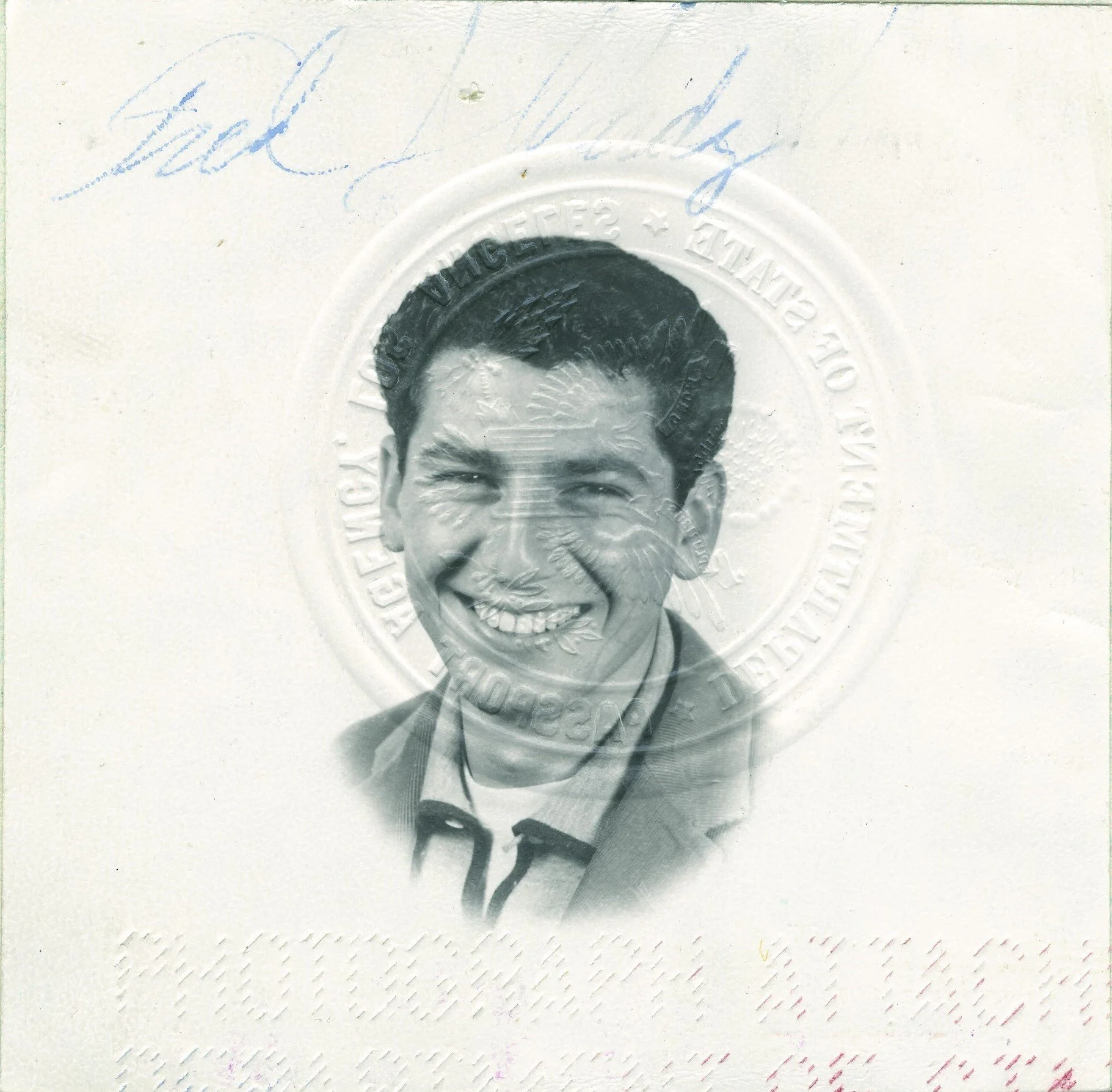

Fig. 6: Passport photograph of Wardy,

summer of 1958.

Fig. 7: Wardy in St. Peter’s Square, Rome,

summer of 1958.

Wardy traveled by train and bus or hitchhiked, staying in youth hostels as he sought out art. He remembers being “so moved” by the sculpture of Rodin, which he saw in Paris, and being attracted to works by the American abstract expressionists Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline in special exhibitions. He recalls thinking that he “had to do something in this area” even though he “did not fully understand yet what art was all about.”

Back from Europe, Wardy began to teach himself how to make balsa wood surfboards in his grandparents’ garage and backyard and, working alone, was soon selling them over the backyard fence. As his boards became known, he sold as many as he could make. He took a sojourn in the spring of 1959 when he went to Honolulu to enroll in philosophy courses at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. He also got a job selecting balsa for wood boards for a surfboard maker with a shop near Waikiki where, in his words, “I surfed whenever I wanted.”

Wardy Surfboards:

Shortly after returning to California from Hawaii in 1959, Wardy established Wardy Surfboards in Laguna Beach and in time hired a staff whom he coached to become as much of a perfectionist as he was. He worked long hours, overseeing every aspect of his business, which also involved research on and development of new ways of making boards. He created striking and unique imagery and texts for advertisements in surfing magazines, including Surfer, a leading magazine of its type, first published in 1960. Upon request from Surfer in 1964 and 1965, Wardy wrote two short essays, “The Lure of the Sea” and “Surfing Is,” the latter also produced by Surfer as a limited-edition large poster.

Eventually, Wardy’s boards were sold in his own shops in Laguna Beach, Pasadena, Honolulu, San Francisco, and Copiague, Long Island. The boards were also featured in many other shops, including ones in Florida. Wardy boards were known for the quality of their design, balance, functionality, use of line and color, and aesthetics in general.

Fig. 8: Wardy and his employees at Wardy Surfboards, Laguna Beach, CA, 1962, photograph by Ron Stoner.

Early art career:

Wardy began making paintings in 1963 in his shop after hours and in his auxiliary workspace in Laguna Beach. He produced large and small works using colored polyester resin and sold many at the popular Festival of the Arts of Laguna Beach. An attendant maintained Wardy’s booth while he worked on surfboards at his nearby shop. He has explained the connection between the boards and the paintings: “I took some of the info on surfboards. I applied it to painting, and it did not take long. It was a very interesting thing that I knew how to paint because I’d done stuff in surfboards. Instead of fiberglass, I used cardboard, and the paintings were coming out quite nice.”

By 1966, Wardy knew he wanted to be an artist full time. He sold his company and began taking studio and other classes in Los Angeles at Chouinard Art Institute, which had been merged with the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music in 1961 to become the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). Chouinard, as it was still called, was known for the quality of its faculty and students, hence a good place, in Wardy’s estimation, to study “if you wanted to be a serious painter or sculptor.”

Wardy found his teachers stimulating, especially Philip Leider, who had been a founding editor of Artforum magazine in 1962 and was its editor-in-chief until 1971. Leider’s teachings on how to think about art inspired Wardy, who says that he “had never encountered such ideas before” and that Leider “brought the subject to life and had a different angle on what art was really about.”

When Wardy arrived at Chouinard, music was also on his mind. While making surfboards, he had begun playing classical pieces on the guitar after being inspired by the guitar proficiency of one of his weekend workers at Wardy Surfboards, Frank Robertson. A surfer who wanted to be a writer, Robertson may have given Wardy his first guitar. Wardy was soon traveling north to take classical guitar lessons in Los Angeles with a respected teacher, Lonnie Cothran, who was “very patient.” Wardy’s love of music had begun as a young boy. His grandfather had played French horn with a symphony orchestra in Mexico, and the family home had often been filled with classical and Spanish music on the radio as Wardy grew up. He also remembers being thrilled when taken to concerts given by Andrés Segovia in Los Angeles. Because Wardy was taking on increasingly difficult pieces on the guitar, he looked into the music programs at CalArts. His proficiency won him a coveted place in a master class with the Brazilian composer and classical guitarist Heitor Villa-Lobos. To Wardy’s great disappointment, the school canceled the class. No other students had qualified.

Wardy continued to practice assiduously as he would for the next fifty plus years. Although he did not study music composition at CalArts, he wanted to understand it, specifically “how something so complex could be put together to create such harmony.” Complexity and overall harmony turned out to be important characteristics of many of his artworks.

Wardy’s art studio was in a commercial building in downtown Los Angeles near Chinatown. For large and small paintings, he continued to use colored polyester resin, as he had done in Laguna Beach for surfboards and his first paintings, and for the large, shaped wood reliefs that he also began producing. Wardy had gotten to know the building’s owners and was given the keys to their carpentry works on the next floor so that he could use saws and other equipment during off hours to cut the necessary shapes for the reliefs.

Fig. 9: Façade of the building in which Wardy had his first studio, near Chinatown in Los Angeles, Nov. 1967.

The company made finely crafted desks that Wardy has often recalled. After working with wood in making many of his surfboards, he was attuned to woodworking and developed an admiration for the work of fine craftsmen and artists using wood in skillful ways. Among the books that he has regularly enjoyed is The Soul of a Tree: A Woodworker’s Reflections by George Nakashima, first published in 1981. Examples of Wardy’s painted wood reliefs can be seen in Categories 1 and 2. Selections from later sculpture series using cut wood are in Categories 25 and 26.

In 1968 and 1969, wanting to learn steel and other metalworking techniques, including the handling of heavy-rigging equipment for building large sculptures, Wardy worked at a Los Angeles company that bent steel piping and made cast iron machinery parts. He was glad to work without wages, but his employer soon insisted on paying him. At the company’s facilities, he was additionally given the opportunity to construct sculptures, including six large steel pieces, some as big as 10 by 6 feet, and innumerable smaller pieces in steel and iron. (See Category 1.)

Wardy made another trip to Europe in 1968 to focus on art and to better understand art history. Today, his stack of art history books to read, reread, or peruse is matched in height only by his stack of books on philosophy.

Wardy’s early work met with critical attention. In 1967, he became affiliated with the Los Angeles Art Association Gallery and in 1968 and 1969 with the Nicholas Wilder Gallery, also in Los Angeles. In September 1970, he participated in a group show at the Pasadena Art Museum.

New York City years as an artist:

Encouraged by his success in Los Angeles, and drawn by the burgeoning art scene in New York City, Wardy moved to Manhattan in early 1970. Through an artist friend, he found employment at Turnbuckle, Inc., a Brooklyn city planning firm where he helped produce designs for concrete playgrounds for vest-pocket parks, then a new element of many New York City neighborhoods.

After returning to Los Angeles for several months for family matters later in 1970, Wardy returned to New York and unexpectedly found a job at the Whitney Museum of American Art at its first location on Madison Avenue. Walking by a “magnificent building,” he went in and discovered that it was a museum. He first looked at the art and then asked to be directed to the human resources office. The person in charge hired him as an art handler/preparator, a job which included framing.

He lived briefly at Westbeth, which had recently opened with artists’ live-work spaces. Undeterred by his relative lack of space and limited residency, Wardy embarked on an ambitious series of large paintings. Soon he found two rooms to live and work in, on separate floors, in a small, almost empty office building in Lower Manhattan on what would soon be part of the World Trade Center site. (See Category 2.)

Within a year, Wardy and a group of fellow artists moved to a five-floor building not far away on Thomas Street, between West Broadway and Church Street, in part of a neighborhood later known as Tribeca. Many of its former industrial buildings were being converted into lofts for artists as work and living spaces. Wardy and most of the original group in the building later purchased it. Believed to date from the 1870s, the Thomas Street building was first owned by a twine company, which had stored immense spools of twine on the ground floor. This was the space that Wardy chose. With its extension beneath a skylight at the back, it was the largest floor in the building at 2,497 square feet. It also had the highest ceilings, over 12 feet.

Fig. 10: Wardy with his daughter, Meredith, about May 1986, at the outer doorway of 70 Thomas Street. The door to his studio is open behind them.

The cavernous space provided plenty of room for working on and hanging large paintings as well as separate areas for creating works on paper and sculpture. From the start, it also served as a showplace for art dealers and buyers to see Wardy’s ongoing and prolific output. One step up from the sidewalk, the ground floor allowed easy ingress of supplies (such as wood for stretcher bars and crates) and egress of artworks. For decades, Wardy kept his studio bare and strictly for work, the only amenities being a utility sink and toilet, both unwalled, and a chair. According to Wardy, “Nothing can be done without solitude. Making art is a lonely business.”

While working at the Whitney from 1970 to 1972, Wardy met many artists, curators, and critics who encouraged him as an artist. The Whitney Painting Annual of 1972 exhibited one of his current acrylic paintings. (See Category 3 for the type.) Because the art handlers were not paid overtime but were asked to work long hours, Wardy contacted the Teamsters and worked with a representative in organizing the art handlers to join the Teamsters Union. This was the beginning of unions at the Whitney.

In late 1972, a prominent Whitney curator, James Monte, recommended Wardy to the United States Information Agency (USIA) for a curatorial and teaching position. It involved traveling to Japan with an exhibition of works by contemporary American sculptors, overseeing its installation at various locations, and lecturing about it and other aspects of American art. From January into April 1973, Wardy spoke at universities and art schools throughout the country, including in Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka, and Nagoya. The exhibition was shown at USIA centers, where Wardy also gave talks. During his stay, he was invited to go to the studios of potters who were considered National Treasures. The extraordinary quality of their work inspired him, and their quiet demeanor and humble circumstances touched him.5

Fig. 11: Wardy lecturing at the American Center in Nagoya, Japan, through the auspices of the USIA, Feb. 19, 1973, seen here in the Mainichi Shimbun (Daily Newspaper).

In 1974, the Arnot Art Museum in Elmira, New York, commissioned Wardy to create an outdoor sculpture with funds from the New York State Council for the Arts. He and museum staff members built the work, consisting of large blocks of wood, on the lawn of the museum. For a time, he was also artist-in-residence there and gave instruction on sculpture techniques. (See Category 3 for other photographs.)

Fig. 12: Wardy in the center working with a crew from the Arnot Art Museum, Aug. 13, 1974. (Other photographs of the installation of this piece are in Category 3.)

Representation and reviews:

Willard Gallery in New York began to represent Wardy in the early 1970s, and he had his first one-man show there in 1974. Other solo and group shows followed. As part of group shows, Willard sent Wardy’s work to other cities, including Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Antonio. Located on Madison Avenue and 72nd Street, Willard was one of New York’s most prestigious and historically significant galleries. Marian Willard Johnson, its longtime owner, was known for identifying new talent and for her associations with many prominent artists throughout her long career. She had given the American sculptor David Smith his first solo show in New York in 1938 at her first gallery. At the time of Wardy’s association with Willard Gallery, it also showed such well-known artists as Mark Tobey and Morris Graves. Among artists whom Wardy helped to introduce to the gallery were the California painter Llyn Foulkes, the American sculptor Randy Hardy, and the Swiss-born painter Pierre Haubensak.

In 1976, Galerie Veith Turske in Cologne, Germany, also began to represent Wardy. Turske invited him to live and work in Cologne for several months in 1977 to produce works for pending exhibitions and sales. Wardy’s work was also exhibited in numerous museums and galleries in other European cities, and at several international art fairs, including ones in Bologna and Dusseldorf.

At an exhibition in 1982 at the M. Knoedler Gallery in Zurich, works by Wardy joined ones by such major figures as Alexander Calder, David Smith, Frank Stella, and Robert Motherwell. Wardy’s association with Galerie Veith Turske continued until it closed in the 1980s.

The first critical reviews of Wardy’s work at Willard helped to establish him within the art world and brought his art to the attention of many collectors. Reviews by critics included ones by Thomas Hess, in The New York magazine; John Canaday and Hilton Kramer in The New York Times; Judith Tannenbaum in Arts Magazine; and Phyllis Derfner in Art International. According to Kramer (The New York Times, March 25, 1977), reviewing a solo show at Willard Gallery:

Vertical abstract paintings that are constructed of irregular, rough-edged bands of intense color are what Frederick Wardy has now turned his talents to—an abrupt change from the black and white pictures he so recently produced [See Category 6.] Yet perhaps the change is not really so abrupt after all. Even in this energetic assault on the color field style, it is still a graphic use of “line”—which dominated the black and white pictures—that gives the new paintings their power. Only now we see the sometimes harsh, sometimes lyrical effects of light dissolving and transforming this “line” into a more melodious continuum of color. We feel ourselves in the presence of an artist moving fast, and appropriating whatever territory interests him at the moment.

The last sentence of this review is significant considering Wardy’s large output throughout his career: his twenty-nine abstract stylistic periods and many miscellaneous works. His love of seeking out new experiences and exploring new skills, as well as his consistent energy, reveal themselves in this output and in his use of many mediums.

Fig. 13: Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 6'3″ x 5'.

Wardy has frequently expressed excitement over creating art. In many notebooks, has written down his thoughts about art. This includes, “making art is a great joy,” “the essence of art is to have pleasure in giving pleasure,” “true innovation comes from artists steeped in tradition,” and “I’ve jammed myself full of art history.”

Wardy’s work has entered many institutional and private collections, including those of the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.; the Minnesota Museum of Art, Saint Paul; the San Diego Art Museum; the Sprengel Museum, Hanover, Germany; and the Neue Galerie der Stadt, Linz, Austria. Since the late-1980s, Wardy’s work has been represented by private dealers and sold directly by him from his studio.

Recent observations by Wardy on the New York art scene:

In response to questions related to a forthcoming article on his surfboard making years and his time as an artist, Wardy responded as follows:

“New York was and still is the art capital of the world, with many great museums and the bulk of major artists. That does not mean that if you produced art in New York that it was good, however. There were many opportunities for exhibiting and selling, perhaps matched only by Paris. The number of artists and galleries was overwhelming.”

“I got my first job in New York at the Whitney Museum of American Art as a preparator for exhibitions and had a firsthand view of many artworks. I spent a lot of time looking at works in the storage units and of course at the many exhibitions at the Whitney and elsewhere in the city.”

“There were many opportunities to meet great artists, including Willem de Kooning, Jim Dine, and Peter Agostini, and to see and discuss their work them in their studios. The generosity of artists willing to show me their art and their encouragement helped to open the New York art world to me. Meeting so many artists was an enriching experience. The number of artists who were successful was just amazing. Their work went out into the world. You could go to bars where artists congregated, but you did not have to drink, just talk. There was such openness. As time went on, the New York art scene grew even larger, and you could continue to see art of every range, everything from conceptual to abstraction and more. The more you look at art, it not only gives you pleasure but makes you become a better artist.”

West Coast years: In the early 1980s, Wardy began spending summers on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State, near the small town of Sequim. His residence had views of the Strait of Juan de Fuca with Vancouver Island, Canada, in the distance, and the Olympic Mountains to the south. For several years, his summer studio was a large room in the Dungeness School, a Washington State Historical Site that is on the National Register of Historic Places. There he created large and small acrylic paintings, which were shipped to New York, as well as works on paper, including some with new combinations of mediums.

Fig. 14: View of the Dungeness School, Dungeness, WA, summer of 1986.

Fig. 15: Wardy with his daughter, Meredith, in his second-floor studio in the schoolhouse, summer of 1986.

With his work continuing to sell through private dealers or from his New York studio, Wardy spent more time working in Sequim beginning in the late 1990s. His output included not only paintings and works on paper but also three series of sculpture. Two of these required small-scale woodworking techniques. (See Categories 25 and 26.) He learned the techniques from a local master carpenter, who gave him space in his shop to assemble his works.

Currently:

Since 2016, Wardy has lived and worked in both New York City and Long Beach, California. He has been married to Trudie Grace, an art historian, since 1980. They have a daughter, Meredith Wardy, and two grandchildren.

Fig. 16: Wardy at his worktable in Long Beach, CA, 2018.

Fig. 17: A work in progress on Wardy’s worktable in Long Beach, 2018.

Fig. 18: Wardy in his backyard in Long Beach, Sept. 2022.

Artwork and Wardy Surfboards (plus appendices) in this website:

•Artwork (selected works grouped by style and chronology)

•Wardy Surfboards (an essay with photographs of Wardy boards; advertising imagery and writings by Wardy; published and unpublished writings by others about Wardy boards, and related material)

•Appendices of Wardy Surfboards (A: images in the essay; B: photographs of Wardy boards, including those from the text; C: observations about Wardy Surfboards by writers on surfing and others; D: selected writings by Wardy in magazine advertisements in chronological order; E: selected images by Wardy in magazine advertisements in chronological order; F: essays by Wardy, “The Lure of the Sea” and “Surfing Is”

A recent article:

Lance Conragan, a longtime surfer and surfboard design aficionado, has written an article that explores Wardy’s surfboard making years and his decades as an artist. Entitled “Uncommon Skill & Meticulous Attention,” it has been published in The Surfer’s Journal (32.3, June/July 2023).

Footnotes:

1. All quotes from Wardy are based on interviews by the author in 2022 and 2023.

2. When Wardy returned to Highland Park, he often took riding lessons in Griffith Park at the DuBrock Stables, which later became part of the Los Angeles Equestrian Center

3. The quotation from 1947 comes from Highland Park News-Herald & Journal (Oct. 17, 1963).

4. The Mr. and Mrs. George Gard De Sylva Collection, which included major works by Cézanne, Redon, Gauguin, Modigliani, Morisot, Picasso, and Van Gogh, was given to the Los Angeles County Museum in 1946. Wardy may have seen works from it.

5. The Mainichi Shimbun (Daily Newspaper) was one of the largest newspapers in Japan at the time. This article is from the Evening Edition, Feb. 19, 1973.